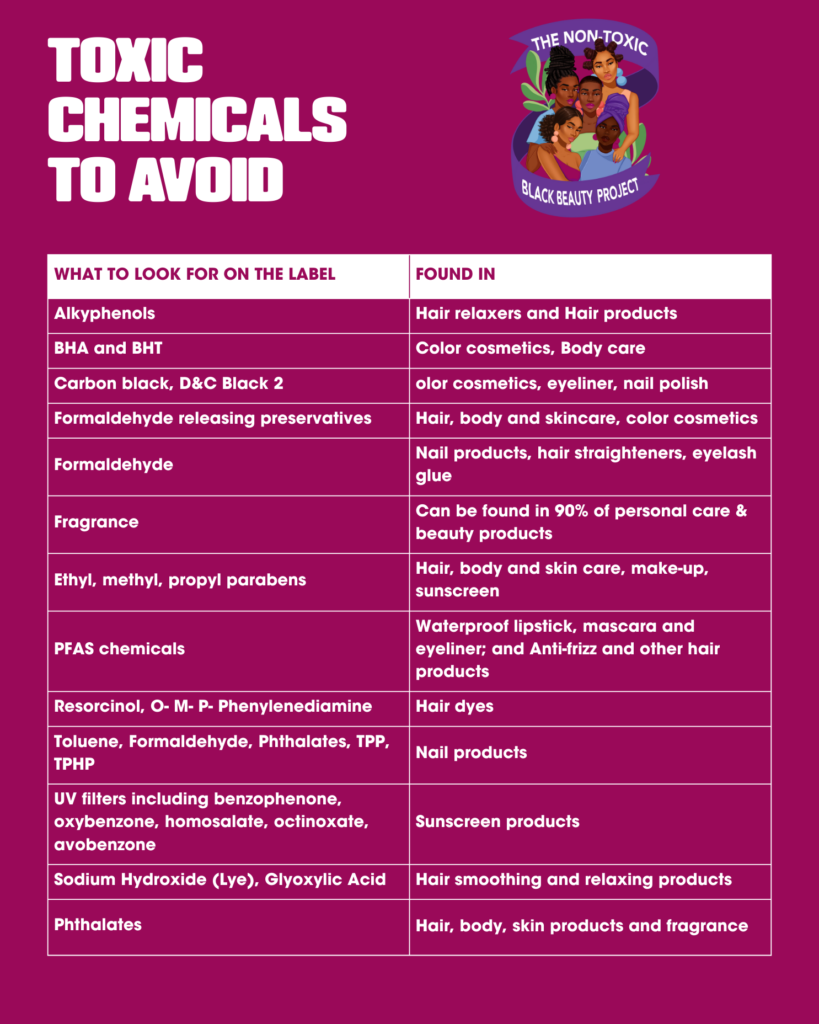

Formaldehyde and formaldehyde-releasing preservatives (FRPs) are used in many personal care products,[1] particularly in hair products including straighteners, nail products, body and skincare products, and liquid baby soaps.

These chemicals, which help prevent microbes from growing in water-based products, can be absorbed through the skin and have been linked to cancer and allergic skin reactions.

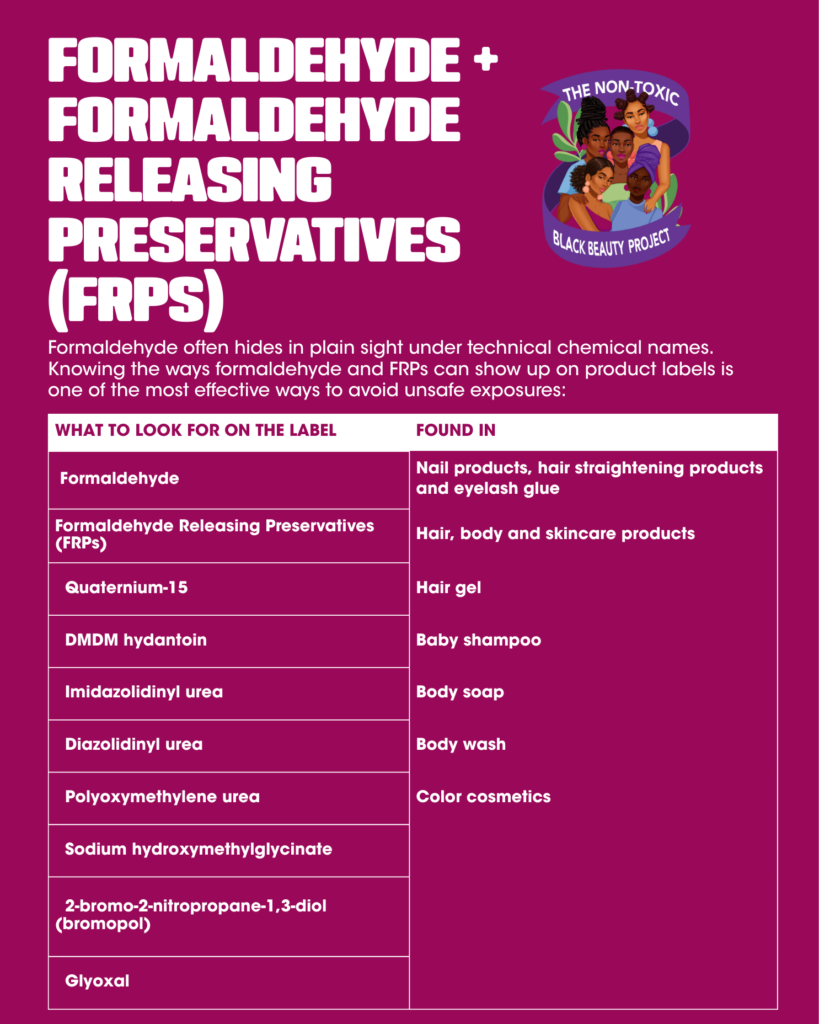

WHAT ARE FORMALDEHYDE-RELEASING PRESERVATIVES AND WHERE ARE THEY FOUND?

Formaldehyde is a colorless, strong-smelling gas used in a wide range of industries and products including building materials, composite wood, glues, paints, preservatives, fertilizers, and personal care products. [2]

In personal care products, formaldehyde is added to products to extend their shelf life. Alternatively, formaldehyde releasing preservatives are commonly used for the same purpose. [3][4] These preservatives release small amounts of formaldehyde over time. Since low levels of formaldehyde can cause health concerns at 250 parts per million (ppm) [5] 200 ppm in sensitized individuals, [6] the slow release of small amounts of formaldehyde are cause for concern.

Some of the most common examples include:

Quaternium-15 is the most sensitizing of these FRPs and is found in blush, mascara, lotion and shampoo.[7]

DMDM Hydantoin is found in skincare, hair products, sunscreen, and make-up remover and is one of the least sensitizing of the FRPs.[8]

Imidazolidinyl urea, diazolidinyl urea, and polyoxymethylene urea, are found in skincare, shampoo, conditioner, blush, eye shadow, and lotion and are all known human allergens.[9] Imidazolidinyl urea is one of the most common antimicrobial agents used in personal care products and is often combined with parabens to provide a broad spectrum preservative system [10] Diazolidinyl urea releases the most formaldehyde of any FRP.[11][12][13]

Sodium hydroxymethylglycinate is found in shampoo, moisturizer, conditioner, and lotion. Animal studies have shown that sodium hydroxymethylglycinate has the potential for sensitization and dermatitis.[14]

Bromopol is found in nail polish, makeup remover, moisturizer and body wash. Bromopol is considered safe in concentrations less than 0.1%. but should not be used in formulations with the FRP amine. Mixing bromopol and amines produces nitrosamines which have been found to penetrate the skin and are linked to cancer.[15]

Glyoxal is found in conditioner, lotion, nail polish and nail treatment, and is a skin allergen.[16]

What Levels Are Present in Products?

A recent 2023 study by Washington State Department of Ecology detected formaldehyde levels ranging from 39.2 ppm to 1,660 ppm among various body lotions and hair products. [17] The highest levels of formaldehyde were found in hair styling gels and creams, many of which are marketed towards Black women with innocuous “free of” claims. Shine ‘n Jam Extra Hold Conditioning Styling Gel, a popular hair styling product containing DMDM hydantoin and used by Black women for “soft waves, locks, braids, twists, edge control and smooth looks” had the highest level of formaldehyde, at 1,660 ppm. Further, concentrations as low as 200 ppm can cause allergic reactions, and this study found that 24 out of 30 products contained formaldehyde above this level. [17] Another study conducted in 2024 also reported formaldehyde levels above 200 ppm in personal care products.[18]

Research led by Silent Spring Institute found that 53% of Black and Latina women use products that contain formaldehyde or formaldehyde releasing preservatives, highlighting the disproportionate exposure to these products marketed to communities of color.[19] Of the 35 products tested, the most common FRPs found were DMDM Hydantoin and diazolidinyl urea. Many of these products are used multiple times per week and are leave-on products (e.g., lotions), which contributes to more longer-term exposure.[19]

Additionally, research indicates that longer storage time and higher temperature increases the amount of formaldehyde released from FRPs and could ultimately lead to more severe health concerns.[20]