Home > Resources > Health & Science > Fragrance Disclosure

Home > Resources > Health & Science > Fragrance Disclosure

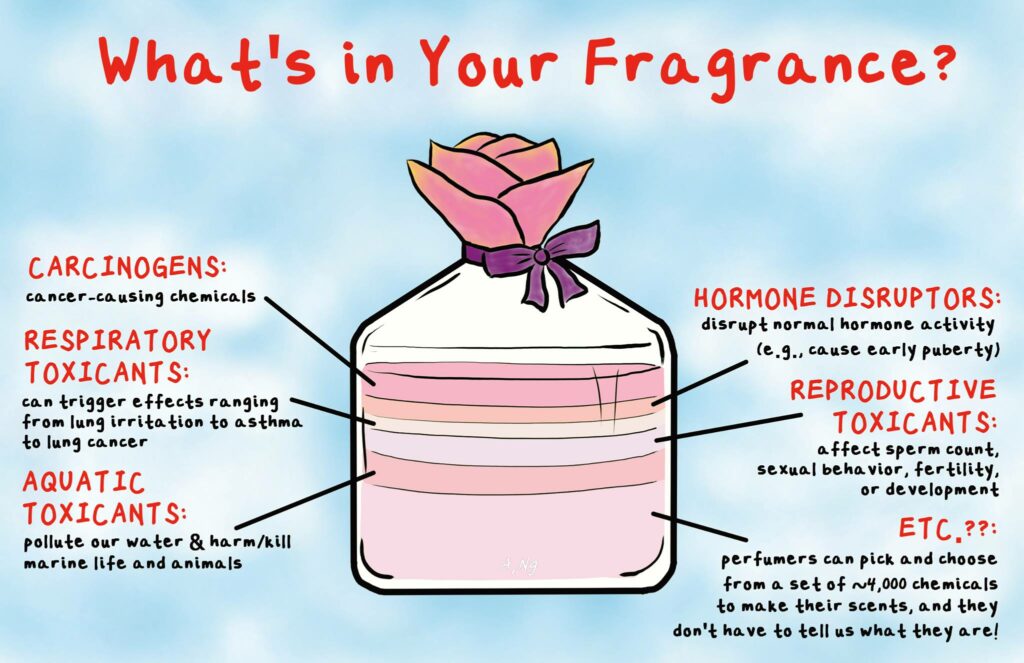

Did you know there are secret, unlabeled, and often toxic fragrance and flavor chemical ingredients in many common personal care products?

Dozens, sometimes even hundreds, of chemicals can hide under one little word – “fragrance” – on the product labels of the beauty and personal care products you use every day. Fragrance suppliers have long enjoyed federal trade secret protections that allow them to hide the ingredients that make your beauty and personal care products smell good.

As a result of trade secret protections, consumers get incomplete information regarding the fragrance and flavor ingredients in their beauty and personal care products. Meanwhile, manufacturers are unable to provide consumers with the full ingredient disclosure they are asking for, and regulators are unable to determine—and ensure—the safety of the full scope of ingredients on the market being used to formulate cosmetics. Fragrance houses and their trade associations are desperately trying to hold on to this special privilege, even as hundreds of cosmetic companies are voluntarily disclosing the fragrance ingredients in their products in response to consumer right to know demands. (See the “Trade Secrets” section below for more)

Breast Cancer Prevention Partners’ 2018 report Right to Know: Exposing Toxic Fragrance Chemicals in Beauty, Personal Care and Cleaning Products found that fragrance chemicals made up the vast majority of the chemicals linked to harmful chronic health effects in the beauty and personal care products tested. The study investigated to what extent major companies that make beauty and personal care hide unlabeled toxic chemicals in their products. BCPP took on this research project because the scientific literature and previous product testing indicated that fragranced products contained chemicals linked to cancer, birth defects, hormone disruption and other adverse health effects.

Unfortunately, consumers looking for fragrance free products have limited options. Even products labeled as unscented may have fragrance added to mask the smell of other ingredients.

Hair products are especially problematic: more than 95 percent of shampoos, conditioners, and styling products contain fragrance.[1] Without legally mandated fragrance ingredient disclosure, it is impossible for consumers to avoid potentially harmful ingredients or for researchers and regulators to understand the full universe of ingredients being used to formulate cosmetic products.

In 2021, U.S. Representatives Jan Schakowsky and Doris Matsui introduced the Cosmetic Fragrance and Flavor Ingredient Right to Know Act, which would require companies to disclose fragrance and flavor ingredients that are harmful to human health or the environment on their product labels and websites. Fragrance ingredient disclosure will allow consumers to make safer and more informed decisions, benefit manufacturers who want to practice a higher level of transparency and provide regulators with the information they need to more effectively regulate the safety of cosmetic products. This bill is one of four bills that make up the Safer Beauty Bill Package, which aims to make personal care products safer for everyone.

In October 2020, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed the California Cosmetic Fragrance and Flavor Ingredient Right to Know Act of 2020 (SB 312) into law. This first of its kind law requires companies that sell beauty or personal care products in California to report fragrance or flavor ingredients linked to harm to human health or the environment to the California Department of Public Health by January 1, 2022, which then makes that information publicly available through its Safe Cosmetics Program online database. Learn more >

[1] Scheman, A., Jacob, S., Katta, R., Nedorost, S., Warshaw, E., Zirwas, M. and Bhinder, M. (2011) Hair products: Trends and Alternatives: Data from the American Contact Alternatives Group. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology, 4(7), pp. 42- 46.

Fragrance allergies affect two to 11 percent of the general population.[1],[2] This translates to tens of millions of people globally affected by fragrance. Fragrance chemicals can become major sensitizers through air oxidation, photo-activation, or skin enzyme catalysis or cross-sensitizing – a process by which a person becomes sensitized to substances different from the substance to which the person is already sensitized.[3] Once sensitized, the only way to prevent the development of a severe, irreversible allergy is to avoid further exposure.

Since fragrance ingredients are volatile, they easily enter the air as gases and expose the eyes and naso-respiratory tract. For asthmatics, the effect of exposure may be more severe. Like second hand smoke,[7] even low concentrations of fragrance ingredients can provoke asthmatic episodes.[8] Inhalation exposure to common sanitizing agents called quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) has been linked to occupational asthma.[9] Other common fragrance ingredients such as benzyl salicylate, benzyl benzoate, butoxyethanol are known skin, eye, nose and throat irritants which can cause severe symptoms such as a burning sensation, nausea, vomiting and damage to the liver and kidneys.[10],[11],[12] European Union’s Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety has identified the fragrance ingredients cinnamal and citral as “established contact allergens in humans.”[13]

In 2011, the International Fragrance Association (IFRA) published a list of 2,339 possible fragrance materials used by IFRA affiliated members, including fragrance suppliers, who use chemicals from this list or “palette” of ingredients to formulate fine fragrances and fragranced cosmetics and personal care products.[14] The IFRA list of possible fragrance ingredients includes chemicals listed as carcinogens by California’s Prop 65 Program and the National Toxicology Program (NTP) such as pyridine, benzophenone, methyleugenol and styrene.[15]

In a 2010 study, 17 tested fragrances contained an average of four hormone-disrupting ingredients each, including synthetic musks and diethyl phthalate.[16] Synthetic musks mimic and displace natural hormones, which can potentially disrupt important endocrine and biological processes.[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22] High levels of musk ketone and musk xylene in women’s blood may also be associated with gynecological abnormalities such as ovarian failure and infertility.[23] These findings provide human evidence for findings that suggest endocrine disruption in other species.[24] In another example of endocrine disruption, diethyl phthalate has been linked to unusual reproductive development in baby boys and sperm damage in adult men.[25],[26],[27]

In 1986, the National Academy of Sciences targeted fragrance as one of the six categories of chemicals that should be given priority for neurotoxicity testing.[28] Since then, animal studies have linked fragrance ingredient p-cymene to headache, weakness, and irritability, along with the reduction in number and density of brain synapses.[29] In addition, research has shown that the synthetic musks tonalide and galaxolide induce brain cell degeneration, which can lead to degenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease.[30]

Fragrance represents a serious threat to the environment. Synthetic musks end up in wastewater, drinking water, soil, and indoor air. Musk also bio-accumulates in the fatty tissue of aquatic wildlife, and travels through the food chain into salmon and shrimp.[31] In a 2010 study of fragranced products, each product emitted volatile organic compounds that have been identified as toxic or hazardous under federal law. Despite releasing compounds like chloromethane and methylene into the air, fragrance remains unregulated.[32] The continual contamination of our air, soil and water resources has even identified some fragrance chemicals as persistent organic pollutants (POPs).

[1] Schnuch, A., Lessmann, H., Geier, J., Frosch, P.J., and Uter, W. (2004) Contact allergy to fragrances: Frequencies of sensitization from 1996 to 2002. Results of the IVDK. Contact Dermatitis. Vol. 50. pp. 65-76. 2004. & Schafer, T., Bohler, E., Ruhdorfer, S., Weigl, L., Wessner, D., Filipiak, B., Wichmann, H.E., and Ring, J. (2001) Epidemiology of contact allergy in adults. Allergy. Vol. 56. pp: 19992- 1996.

[2] Cheng, J., and Zug, K. (2014). Fragrance Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Dermatitis, 25(5), pp. 232-245.

[3] Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety. (2012) Opinion on Fragrance Allergens in Cosmetic Products. European Commission. pp. 33-38.

[4] Cheng J, Zug K. (2014) Fragrance Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Dermatitis, 25(5), pp. 232-245.

[5] Contact dermatitis. American Academy of Dermatology. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/eczema/types/contact-dermatitis/causes. Accessed online May 3, 2022.

[6] Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety. (2012) Opinion on Fragrance Allergens in Cosmetic Products. European Commission. pp. 7-9.

[7] Institute of Medicine. (2000) Clearing the Air, Asthma and Indoor Air Exposures, Executive Summary. p. 9.

[8] Kumar P., Caradonna-Graham V.M., Gupta S., Cai X., Rao P.N., and Thompson, J. (1995) Inhalation challenge effects of perfume scent strips in patients with asthma. Annals of Allergy Asthma Immunology, 75, pp. 429-433.

[9] Purohit, A., Kopferschmitt-Kubler, M.C., Moreau, C., Popin, E., Blaumeiser, M., and Pauli, G. (2000) Quaternary ammonium compounds and occupational asthma. International archives of occupational and environmental health, 73(6), 423-427.

[10] Opinion concerning fragrance allergy in consumers. Scientific Committee on Cosmetic Products and Non-Food Products Intended for Consumers. European Commission. (1999) http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_risk/committees/sccp/documents/out98_en.pdf. Accessed online May 3, 2022.

[11] Toxnet. Benzyl Benzoate. Toxicology Data Network. (2003) http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search/a?dbs+hsdb:@term+@DOCNO+208.

[12] CDC. Butoxyethanol. NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. (2015) http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0070.html. Accessed online May 3, 2022.

[13] Opinion on Fragrance Allergens in Cosmetic Products. Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety. European Commission. (2012) pp. 7-9.

[14] IFRA Ingredients. (2015) https://ifrafragrance.org/priorities/ingredients Accessed online May 3, 2022.

[15] Report on Carcinogens, Thirteenth Edition. NTP (National Toxicology Program). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. (2014)

[16] Not So Sexy: Hidden Chemicals in Perfume and Cologne. EWG. (2010)

[17] Petersen, K., and Tollefsen, K. (2011) Assessing combined toxicity of estrogen receptor agonists in a primary of culture of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) hepatocytes. Aquatic toxicology, 101, pp. 186-195.

[18] Gomez E, et al. (2005) Estrogenic activity of cosmetic components in reporter cell lines: parabens, UV screens, and musks. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, 68, pp. 239-251.

[19] Simmons D, Marlatt V, Trudeau V, Sherry J, Metcalfe C. (2010) Interaction of Galaxolide® with the human trout estrogen receptor-α. Science of the Total Environment, 408(24), pp 6158-6164.

[20] Yamauchi R, Ishibashi H, Hirano M, Mori T, Kim J-W, Arizono K. (2008) Effects of synthetic polycyclic musks on estrogen receptor, vitellogenin, pregnane X receptor, and cytochrome P450 3 A gene expression in the livers of male medaka (Oryias latipes). Aquatic Toxicology, 90, pp. 261-268.

[21] Witorsch R, Thomas J. (2010). Personal care products and endocrine disruption: a critical review of the literature. Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 40(S3), pp. 1-30.

[22] Schreurs R, Sonneveld E, Jansen J, Seinen W, van der Burg B. (2005). Interaction of polycyclic musks and UV filters with the estrogen receptor (ER), androgen receptor (AR), and progesterone receptor (PR) in reporter gene bioassays. Toxicological Sciences, 83, pp. 264-272.

[23] Eisenhardt S, Runnebaum B, Bauer K, Gerhard I. (2001). Nitromusk compounds in women with gynecological and endocrine dysfunction. Environmental Research Section A, 87, pp. 123-130.

[24] Carlsson G, Om S, Andersson P, Soderstrom H, Norrgren L. (2000) The impact of musk ketone on reproduction in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Marine Environmental Research, 50(1-5), pp. 237-241.

[25] Washington Toxics Coalition. (2008). Earliest Exposures. Retrieved from web.

[26] Hauser, R., Meeker, J. D., Singh, N. P., Silva, M. J., Ryan, L., Duty, S., & Calafat, A. M. (2007). DNA damage in human sperm is related to urinary levels of phthalate monoester and oxidative metabolites. Human reproduction, 22(3), 688-695.

[27] Swan, S. H. (2008). Environmental phthalate exposure in relation to reproductive outcomes and other health endpoints in humans. Environmental research, 108(2), 177-184.

[28] Congress, U. S. (1990). Office of Technology Assessment, Neurotoxicity: Identifying and controlling poisons of the nervous system. OTA-BA-436. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

[29] Lam HR, Ladefoged O, Ostergaard G, Lund SP, Simonsen L. (1996). Four weeks’ inhalation exposure of rats to p-cymene affects regional and synaptosomal neurochemistry. Pharmacol Toxicol, 79(5), pp. 225-30.

[30] Ayuk-Takem L, Amissah F, Aguilar B, Lamango N. (2014). Inhibition of polyisoprenylated methylated protein methyl esterase by synthetic musks induces cell degeneration. Environmental Toxicology, 29(4), pp. 466-477.

[31] Bridges, B (2002). Fragrance: emerging health and environmental concerns. Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 17, pp. 368–369.

[32] Steinemann AC, et al. (2010). Fragranced consumer products: Chemicals emitted, ingredients unlisted. Environ Impact Asses Rev, doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2010.08.002.

Although it’s one word on an ingredient label, “fragrance” can contain dozens, even hundreds, of chemicals. Fragrance manufacturers claim that the specific chemicals used to create their scents are confidential business information, or “trade secrets,” a concept originally codified in the 1966 Federal Fair Packaging and Labeling Act (FPLA). The FPLA prevents the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from compelling manufacturers to disclose the chemical compositions of their fragrances, and instead allows companies to claim trade secret protection for the specific chemicals used in their formulation.[1] Trade secret protections are further codified in the 1979 Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA), a legal framework that states can voluntarily adopt to clarify the definition of trade secrets and strengthened the awarded protections to businesses; 47 states, Washington D.C., the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico have made this framework state or local law.[2] Together, these laws only require manufacturers to label products with fragrance formulations as “fragrance,” “parfum,” or “aroma.”

Fragrance houses base their claim for trade secret protection on the assertion that labeling their products with chemical lists would give away proprietary information known solely to the company. However, UTSA specifically qualifies that trade secrets are, “information … not being generally known to or readily ascertainable through appropriate means by other persons who might obtain economic value from its disclosure or use.”[3] Listing the chemicals on the labels of cosmetics would not reveal information that could not alternatively be derived by “appropriate means by other people,” namely through the process of reverse-engineering, which has become standard practice in the fragrance industry. In other words, the chemicals in fragrance simply no longer qualify as “trade secrets” under the legal definition provided by UTSA. Further, federal and state laws already require the disclosure of ingredients for over-the-counter drugs and cosmetics, among other things and this requirement has not adversely affected these industries.[4] Some cleaning product companies already voluntarily label all, or almost all, of the chemicals that comprise their fragrances, like Seventh Generation[5] and SC Johnson[6] and hundreds of cosmetic companies are also fully disclosing fragrance ingredients.[7]

Despite holes in the trade secret argument, the personal care product and cosmetic industry continues to use this logic to avoid full fragrance disclosure. Without full disclosure of pertinent chemical information, consumers cannot make informed decisions about products they are exposed to daily. In addition, researchers, healthcare providers and regulators cannot understand the full universe of ingredients used to formulate cosmetic products, limiting the breadth of research on chemical safety and subsequent health care and legal policies constructed to protect the general population. The fragrance industry has been trusted to “self-regulate” and test its chemicals for safety through its Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM), but RIFM’s un-generalized findings and methods of analysis are kept secret, preventing a deeper analysis and verification of their findings by those outside the fragrance industry. The UN Global Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (UNGHS) has identified 1,000+ chemicals currently used in fragrance that either qualify for a “danger” or “warning” level classification, and yet only 186 chemicals have been banned for use by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to date.[8]

[1] http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/ucm148722.htm

[2] http://www.uniformlaws.org/LegislativeFactSheet.aspx?title=Trade%20Secrets%20Act

[3] https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/trade_secret. Accessed online May 3, 2022.

[4] http://www.seventhgeneration.com/come-clean/frequently-asked-questions-about-ingredient-disclosure. Accessed online May 3, 2022.

[5] http://www.seventhgeneration.com/ingredients-glossary

[6] http://www.scjohnson.com/en/products/monty/fragrancedisclosure.aspx

[7] Market Shift: The story of the Compact for Safe Cosmetics and the growing demand for safer products, November 2011 by the Breast Cancer Fund and Commonweal, p. 14-15.

[8] https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/part-700/subpart-b. Accessed online May 3, 2022.

Get Involved

The Campaign for Safe Cosmetics works to reduce exposure to harmful ingredients in personal care products, including those hidden in fragrance. We do this through consumer education, corporate accountability campaigns and legislative advocacy, and work with hundreds of partner organizations, businesses, and other allies.

*You’re subscribing to BCPP’s Campaign for Safe Cosmetics email list. We won’t share your information and you may opt out at any time.